- 357 Lê Hồng Phong, P.2, Q.10, TP.HCM

- Hotline 1: 1900 7060

Hotline 2: (028) 3622 8849

Bài tập IELTS Reading: You are what you speak - Phân tích từ vựng

You are what you speak

Does your mother tongue really affect the way you see the world?

Does the language you speak influence the way you think? Does it help define your world view? Anyone who has tried to master a foreign tongue has at least thought about the possibility.

At first glance the idea seems perfectly plausible. Conveying even simple messages requires that you make completely different observations depending on your language. Imagine being asked to count some pens on a table. As an English speaker, you only have to count them and give the number. But a Russian may need to consider the gender and a Japanese speaker has to take into account their shape (long and cylindrical) as well, and use the number word designated for items of that shape.

On the other hand, surely pens are just pens, no matter what your language compels you to specify about them? Little linguistic peculiarities, though amusing, don’t change the objective world we are describing. So how can they alter the way we think?

Scientists and philosophers have been grappling with this thorny question for centuries. There have always been those who argue that our picture of the Universe depends on our native tongue. Since the 1960s, however, with the ascent of thinkers like Noam Chomsky, and a host of cognitive scientists, the consensus has been that linguistic differences don’t really matter, that language is a universal human trait, and that our ability to talk to one another owes more to our shared genetics than to our varying cultures. But now the pendulum is beginning to swing the other way as psychologists re-examine the question.

A new generation of scientists is not convinced that language is innate and hard-wired into our brain and they say that small, even apparently insignificant differences between languages do affect the way speakers perceive the world. ‘The brain is shaped by experience,’ says Dan Slobin of the University of California at Berkeley. ‘Some people argue that language just changes what you attend to,’ says Lera Boroditsky of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ‘But what you attend to changes what you encode and remember.’ In short, it changes how you think.

To start with the simplest and perhaps subtlest example, preparing to say something in a particular language demands that you pay attention to certain things and ignore others. In Korean, for instance, simply to say ‘hello’ you need to know if you’re older or younger than the person you’re addressing. Spanish speakers have to decide whether they are on intimate enough terms to call someone by the informal tu rather than the formal Usted. In Japanese, simply deciding which form of the word ‘I’ to use demands complex calculations involving things such as your gender, their gender and your relative status. Slobin argues that this process can have a huge impact on what we deem important and, ultimately, how we think about the world.

Whether your language places an emphasis on an object’s shape, substance or function also seems to affect your relationship with the world, according to John Lucy, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands. He has compared American English with Yucatec Maya, spoken in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Among the many differences between the two languages is the way objects are classified. In English, shape is implicit in many nouns. We think in terms of discrete objects, and it is only when we want to quantify amorphous things like sugar that we employ units such as ‘cube’ or ‘cup’. But in Yucatec, objects tend to be defined by separate words that describe shape. So, for example, ‘long banana’ describes the fruit, while ‘flat banana’ means the ‘banana leaf’ and ‘seated banana’ is the ‘banana tree’.

To find out if this classification system has any far-reaching effects on how people think, Lucy asked English- and Yucatec-speaking volunteers to do a likeness task. In one experiment, he gave them three combs and asked which two were most alike. One was plastic with a handle, another wooden with a handle, the third plastic without a handle. English speakers thought the combs with handles were more alike, but Yucatec speakers felt the two plastic combs were. In another test, Lucy used a plastic box, a cardboard box and a piece of cardboard. The Americans thought the two boxes belonged together, whereas the Mayans chose the two cardboard items. In other words, Americans focused on form, while the Mayans focused on substance.

Despite some criticism of his findings, Lucy points to his studies indicating that, at about the age of eight, differences begin to emerge that reflect language. ‘Everyone comes with the same possibilities,’ he says, ‘but there’s a tendency to make the world fit into our linguistic categories.’ Boroditsky agrees, arguing that even artificial classification systems, such as gender, can be important.

Nevertheless, the general consensus is that while the experiments done

In boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

1. Learning a foreign language makes people consider the relationship between language and thought. ____

2. In the last century cognitive scientists believed that linguistic differences had a critical effect on communication. ____

3. Dan Slobin agrees with Chomsky on how we perceive the world.____

4. Boroditsky has conducted gender experiments on a range of speakers. ____

5. The way we perceive colour is a well-established test of the effect of language on thought. ____

ANSWER KEY

1. TRUE

2. FALSE

3. FALSE

4. NOT GIVEN

5. TRUE

TỪ VỰNG TRONG BÀI

Plausible /ˈplɑː.zə.bəl/ (adj): có vẻ hợp lý (seeming likely to be true, or able to be believed)

Cylindrical /səˈlɪndrɪkl/ (adj): dạng hình trụ (having a shape like a cylinder)

Designate /ˈdez.ɪɡ.neɪt/ (v): chỉ định (to choose someone officially to do a particular job)

Compel /kəmˈpel/ (v): ép buộc (to force someone to do something)

Peculiarity /pɪˌkjuː.liˈer.ə.t̬i/ (n): tính chất riêng, nét riêng biệt (the quality of being strange or unusual, or an unusual characteristic or habit)

Grapple /ˈɡræp.əl/ (v): vật lộn, chật vật (to fight, especially in order to win something)

Thorny /ˈθɔːr.ni/ (adj): gai góc, hóc búa (A thorny problem or subject is difficult to deal with)

Consensus /kənˈsen.səs/ (n): sự đồng thuận, sự nhất trí (a generally accepted opinion or decision among a group of people)

Pendulum /ˈpen.dʒəl.əm/ (n): con lắc (a device consisting of a weight on a stick or thread that moves from one side to the other, especially one that forms a part of some types of clocks)

Subtle /ˈsʌt̬.əl/ (adj): khôn khéo, tinh tế (achieved in a quiet way that does not attract attention to itself and is therefore good or clever)

Deem /diːm/ (v): cho rằng, thấy rằng (to consider or judge)

Discrete /dɪˈskriːt/ (adj): rời rặc (clearly separate or different in shape or form)

THƯ VIỆN LIÊN QUAN

Reading là một trong bốn phần thi bắt buộc của bài thi IELTS, đây cũng được xem là phần thi thử thách nhất để chinh phục được band điểm cao. Hãy...

Bài viết cung cấp cho đọc giả Bài tập Reading part 3 - Chủ đề: Why fairy tales are really scary tales - Có đáp án

Bài viết cung cấp cho đọc giả Bài tập Reading part 2 - Chủ đề: The Desolenator: producing clean water - Có đáp án

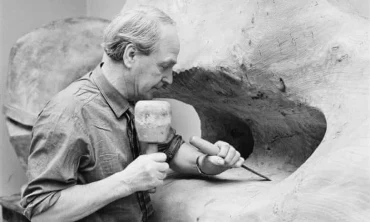

Bài viết cung cấp cho đọc giả Bài tập Reading part 1 - Chủ đề: Henry Moore (1898-1986) - Có đáp án

Hoặc gọi ngay cho chúng tôi:

1900 7060

| Chính sách bảo mật thông tin | Hình thức thanh toán | Quy định chung

| Chính sách bảo mật thông tin | Hình thức thanh toán | Quy định chung

Giấy chứng nhận đăng ký doanh nghiệp số 0310635296 do Sở Kế hoạch và Đầu tư TPHCM cấp.

Giấy Phép hoạt động trung tâm ngoại ngữ số 3068/QĐ-GDĐT-TC do Sở Giáo Dục và Đào Tạo TPHCM cấp